In 2019, the French central government had depleted its annual revenues by November 4, with 58 days remaining in the year. In 2020, this slippage is twice as long, with 114 days of unfunded spending

Paris, November 3, 2020: The Institut économique Molinari has calculated the dates when European Union (EU) member states had spent their entire annual revenues in 2019, along with projections for 2020 and 2021 for France.

THE 6TH ANNUAL EDITION OF THIS STUDY SHOWS THAT IN 2019:

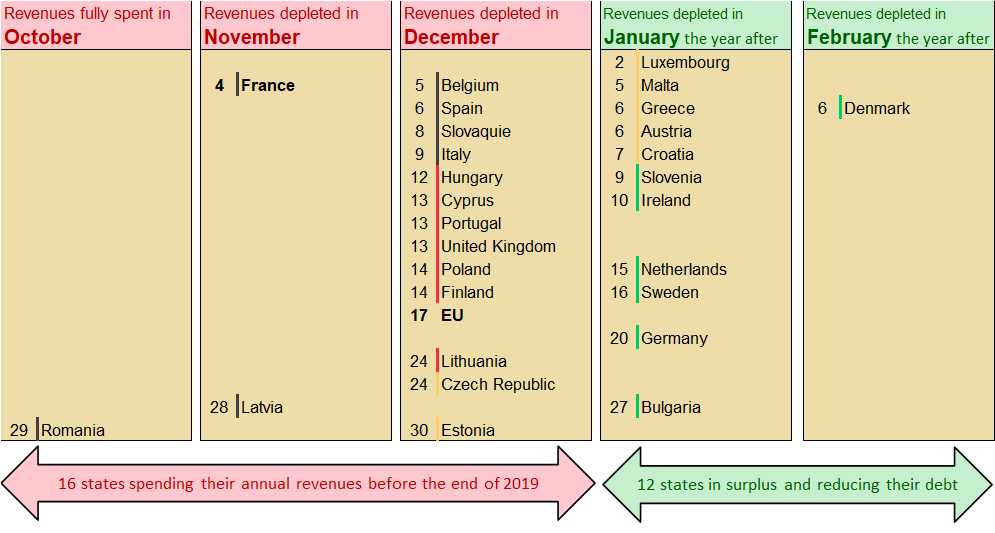

EU central governments had depleted their revenues by December 17 on average, with 15 days left in the year. Among the 28 central governments, 12 were in surplus last year, 13 had depleted their revenues in December and three had spent all their revenues earlier.

Calendar of dates when EU central governments had spent all their revenues

A gap of more than three months between the central governments with the biggest surplus and the biggest deficit:

- Topping the list were Denmark (surplus equal to 36 days of spending), Bulgaria (27 days) and Germany (19 days). Their 2019 revenues covered all spending for the year and provided for debt reduction and/or spending for unexpected events.

- At the bottom were Latvia (deficit equal to 34 days), France (58 days) and Romania (64 days).

- France and Romania are habitual cellar-dwellers. France has been part of the trio of countries furthest out of balance in the last four years, Romania in the last three years.

Central governments, the main source of public deficits in the EU:

- Despite favourable economic conditions, central governments remain the dark spot in European public finances. Across the EU, central administrations produce the lion’s share of public account deficits, with 15 days of unfunded spending over all.

- State-level administrations have been in balance since 2017 and generated four days’ surplus in 2019.

- Local administrations are slightly out of balance, with two days’ deficit last year, bringing them back to the 2013 level.

- Social security administrations have been in balance since 2016 and accrued five days’ surplus last year.

- Public administrations over all had a six-day deficit in 2019, comparable to the 2000 level.

THE FRENCH GOVERNMENT WAS AMONG THE EU’S THREE DEFICIT FRONT-RUNNERS

The French central government had spent all of its revenues by November 4, 2019, with 58 days left in the fiscal year, marking 11 more days of unfunded spending than in 2018.

The gap between France and the EU average was 43 days in 2019. It grew by 12 days between 2018 and 2019, despite favourable economic conditions at the time.

While replacement of the CICE tax credit explained the rise in the central government deficit last year, fiscal consolidation efforts were at a standstill in France even before the Covid-19 crisis hit. France failed to take advantage of growth in 2019, and more generally over the last seven years, to put its public finances in order, unlike what was happening elsewhere in Europe.

A GOVERNMENT INCAPABLE OF REDUCING ITS DEFICITS EVEN DURING AN UPTURN

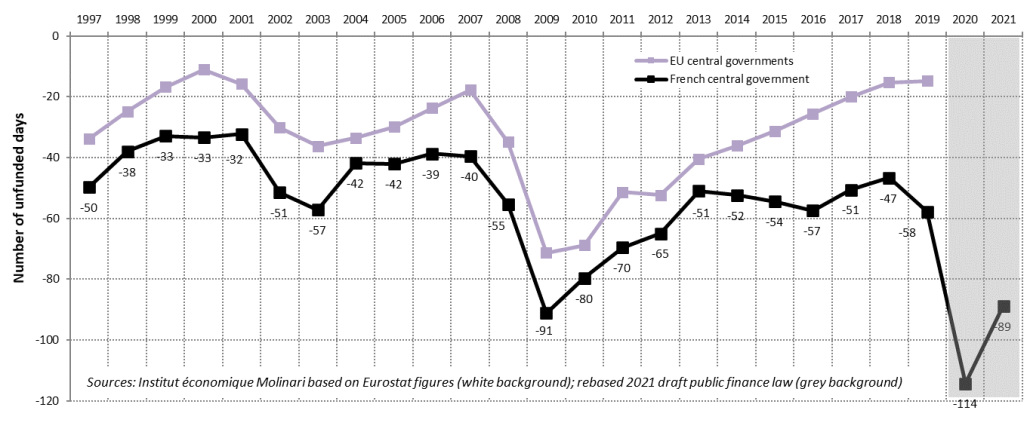

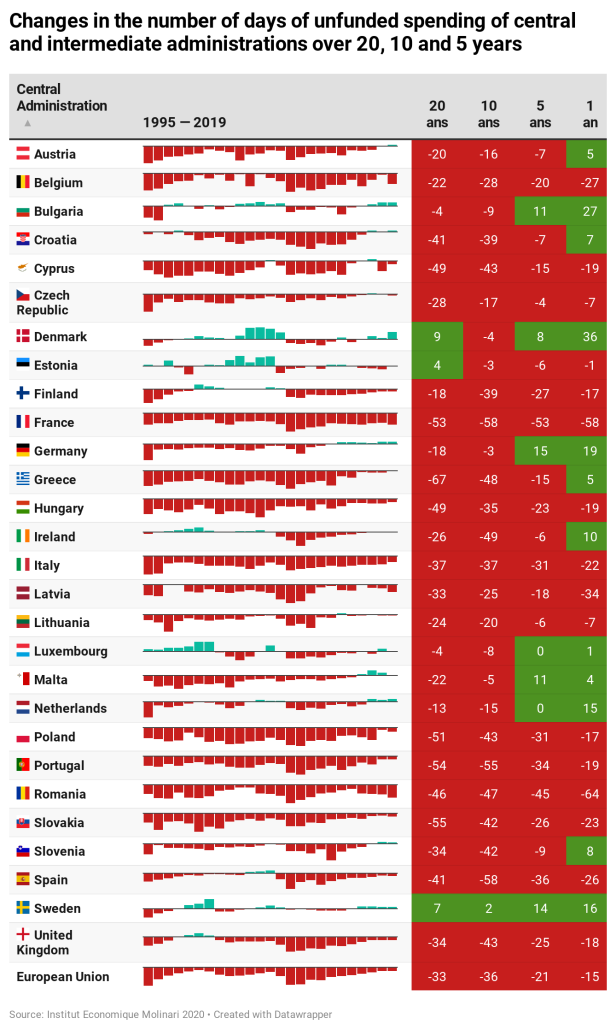

While central governments in the EU have taken advantage of conditions in the last 10 years to reduce their deficits, this was not happening in France. The post-crisis account rebalancing movement begun in 2009 across the European Union came to a halt in France in 2013.

Since 2013, France’s central government has not cut its deficit, even increasing it by seven days.

Meanwhile, EU countries were reducing their deficits by 25 days on average.

An upturn in the late 1970s had enabled France to balance its public accounts, but that situation never recurred in the following decades. Worse yet, phases of improvement were systematically associated with ever-greater imbalances: deficits of about 20 days in the late 1980s, about 30 days in the late 1990s, about 40 days in the late 2000s and more than 50 days last year.

On average, the date when government revenues had been fully spent advanced by 1.5 day per year between 1980 and 2019. Irrespective of cyclical shocks, the French situation has kept deteriorating.

IN 2020 AND 2021, DEFICITS REMINISCENT OF WARTIME

Projections conducted by the Institut économique Molinari show that the French situation is deteriorating significantly: unfunded spending by France’s central government could amount to 114 days in 2020 and 89 days in 2021.

Revenues for the entire year may have been spent by September 8, 2020, and next year’s revenues may have been spent by October 4, 2021, at the central administration level.

Number of days of unfunded spending by the French central administration vs. the EU average

If we limit the analysis to central government accounts within the scope of the public finance law, the budget plight is even more momentous. The year’s entire revenues would have been depleted by July 26, 2020, and 158 days of spending would be unfunded. This threshold of 158 unfunded days has been exceeded only 10 times since the beginning of the 20th century, and only in wartime; from 1914 to 1919, from 1939 to 1940 and from 1944 to 1945. The 2020 deficit, unmatched since the Liberation, is likely to be similar to that of 1920, just after the First World War, with 158 unfunded days. In 2021, the situation may remain ominous, with the year’s revenues depleted by August 29 followed by 124 days of unfunded spending.

THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT GENERATES MOST OF THE FRENCH PUBLIC DEFICIT

The central government’s accounts are in far worse shape than those of other public administrations.

Last year, local authorities in France were in deficit by one day, following three consecutive years of balance. French social security administrations had an eight-day surplus, one day more than the previous year and five days more than in 2017.

Over all, French public administrations taken together depleted their revenues 20 days before the end of 2019.

- This was five days later than the previous year, showing a deterioration.

- Only Britain (21 days of deficits), Spain (25 days) and Romania (44 days) did worse.

In the last 20 years, French public administrations have systematically been in deficit, a characteristic shared only with Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania and Slovakia.

THE FAILURE OF AN ATTEMPT TO RESTORE ORDER TO THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS THROUGH HIGHER REVENUES RATHER THAN THROUGH LOWER SPENDING

The attempt to restore order to the public accounts following the 2007-2008 crisis by relying mostly on taxation has been a failure:

- Two-thirds depended on taxation, with spending cuts accounting for only one-third in France.

- France disregarded the traditional post-crisis phase of reducing public spending. Since the low point of the 2007-2008 crisis, public spending has fallen three times more slowly in France than the EU average. It declined only slightly during the recovery from 2009 to 2019 (-1.6%) while falling significantly in the EU as a whole (-4.4%).

- France attempted to reduce its imbalances by playing the compulsory levy card. Government revenues in France rose at nearly double the EU pace (+2.6% compared to +1.4%).

The EU as a whole has taken a diametrically opposed approach, with an adjustment relying three-quarters on lower spending and one-quarter on taxation.

France has taken what is far from a winning approach. Even before the Covid-19 crisis hit, France had recovered far less financial leeway than the rest of the EU:

- At the end of 2019, the public deficit was four times as high in France (3% of GDP) as in the EU as a whole (0.8% of GDP).

- The 2007-2008 crisis had three times as great an impact on the public finances. Public spending and revenues rose by about three points of GDP, compared to an EU average of one point between 2007 and 2019.

- The persistence of deficits shows the extent of the blockages that need to be overcome to rebalance the public accounts. This suggests that the crisis stemming from Covid-19 poses a very serious danger to French public finances.

RESOURCES

The study, titled “The day European Union governments had spent all their annual revenues,” is available (in French only) on our website.

European graphics (Datawrapper) are provided:

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/nn15r/

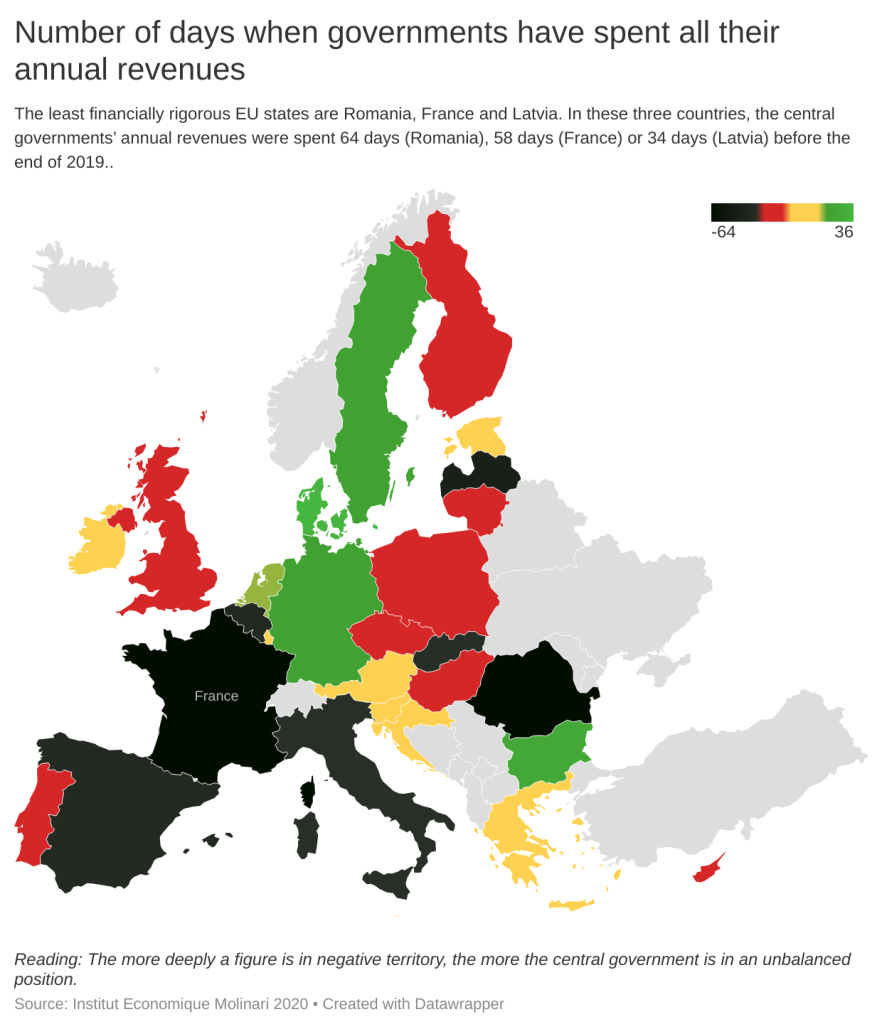

The least financially rigorous EU states are Romania, France and Latvia. In these three countries, the central governments’ annual revenues were spent 64 days (Romania), 58 days (France) or 34 days (Latvia) before the end of 2019.

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/3ub9y/

QUOTES

Nicolas Marques, managing director of the Institut économique Molinari (IEM) and co-author

“In 2020, France’s deficits are doubling, with 114 days of unfunded spending. Covid-19 accounts for only half of this slippage, which is unmatched since 1945. French public finances, suffering from serious comorbidities, were already gravely ill before the pandemic struck.

“The government had depleted its revenues as of November 4, 2019, with 58 days left in the year. By way of comparison, our neighbours depleted their revenues on December 17, barely 15 days before the end of the year.

“Since 1980, every budget has been in deficit, and the date when all the revenues of the central administrations were consumed has slid by 1.5 day per year. The government has become skilled at financial flimflam. It no longer manages to run surpluses enabling repayment of the debts it contracts to finance current expenditures. As a result, the French public debt is spinning out of control. It now amounts to €35,000 per capita, not to mention the €130,000 in implicit debt involving promises made in connection with contributory pension schemes.

“Our southern neighbours’ unfortunate experience during the 2007-2008 crisis showed that a lack of financial leeway leaves countries exposed to social costs and painful adjustments at times of crisis.

“Getting the economy and the public finances back in order should have been the priority in the previous expansion phase. But France was unable to institute a speedy cutback in taxation, thereby weakening its growth. High taxes hurt economic recovery and slowed declines in unemployment. Far from reducing deficits, this amplified the problem, with uncontrolled public spending failing to generate sustainable growth.

“The habit of living from one day to the next, financing current expenditures through debt and high taxes, leaves France exceedingly fragile in this new crisis. The coming years will be difficult. We must hope to learn from past mistakes and to understand that overly high taxes on wealth creation are detrimental to growth.”

Cécile Philippe, president of the Institut économique Molinari (IEM) and co-author

“To cope with the pandemic, not only must we be able to change our mental software quickly but we must also to be able to rely on redundancy. There are many ways to achieve this, in particular by always making sure to maintain financial leeway. Where governments are concerned, this means having reserves in the form of budget surpluses that can be put to use in extreme situations.

“It is hardly surprising to see sound public finances in countries that are handling the health crisis effectively. Germany, with its surpluses, is in a better position to manage the crisis. It is able to mobilise resources quickly and allocate them where they are needed most urgently. France, sad to say, lacks this safety cushion. Since the mid-1970s, despite economic upturns, the public accounts have remained imbalanced, with a very significant gap compared to most other European Union countries. Since the latest financial crisis, France has done more poorly than the rest of the EU in recovering its financial leeway, with the crisis having hit its public finances three times as hard.

“Make no mistake: the absence of budget surpluses is not a trivial or inconsequential matter. It is among the many facets of our unpreparedness. It hurts our responsiveness and our ability to spend at a time when matters of life and death are arising in our public and private health care institutions.”

FOR INFORMATION OR INTERVIEWS, CONTACT:

Nicolas Marques, Managing Director, Institut économique Molinari

(Paris, in French)

nicolas@institutmolinari.org

+ 33 6 64 94 80 61

Or Cécile Philippe, President, Institut économique Molinari

(Paris, Brussels, in French or English)

cecile@institutmolinari.org

+33 6 78 86 98 58

ABOUT THE AUTHORS AND THE IEM

The study was written by Nicolas Marques and Cécile Philippe of the Institut économique Molinari. Both hold doctorates in economics and are, respectively, managing director and president of the institute.

The Institut économique Molinari (Paris and Brussels) is an independent research and education organisation. It seeks to stimulate the economic approach in the analysis of public policy, offering innovative alternative solutions that favour the prosperity of all individuals making up society.