Despite reforms, French competitiveness is still 7% lower for wages net of taxes and 35% lower for corporate profitability.

The Institut economique Molinari is publishing a new ranking of the comparative competitiveness of Europe’s six largest economies, covering both employees and companies. Constructed from official data (Eurostat, OECD, etc.), it offers an unprecedented perspective on the fragility of the French economy in terms of both purchasing power and corporate profitability. France, the leader in taxation on labour and wealth creation, is the least profitable country.

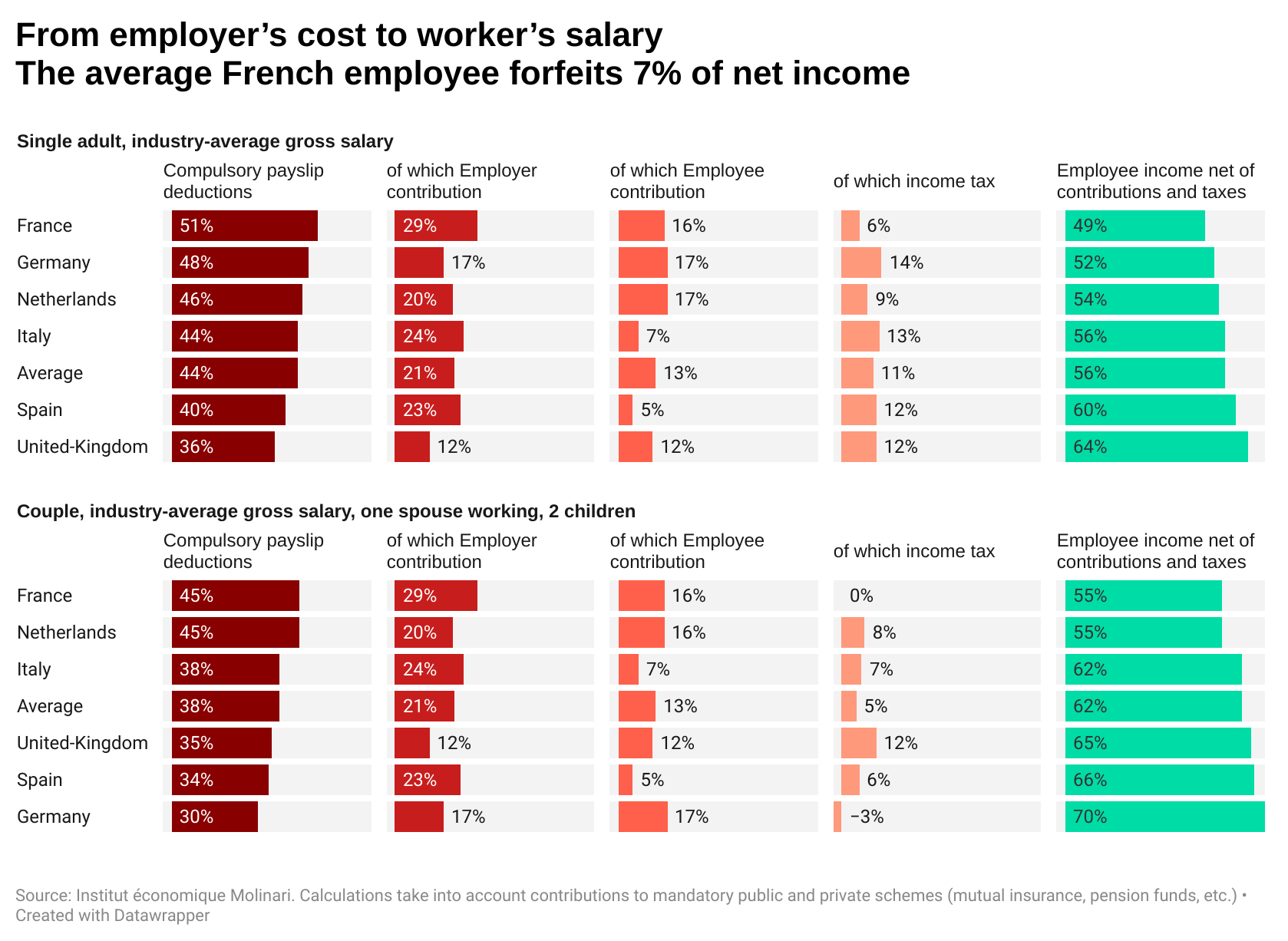

7% less net income after compulsory deductions for the average French worker

For the average unmarried employee without children, compulsory deductions represent 51% of employer costs. This leaves only 49% for earnings net of contributions and taxes, versus an average of 56% among the major European economies. France comes in last, and far behind the UK where employee income net of taxes represents 64% of employer costs.

For an average couple with one unpaid spouse and two children, compulsory levies represent 45% of employer costs in France. This leaves 55% remuneration net of compulsory deductions, compared with an average of 62% among the major European economies. France is tied for last (with the Netherlands) and far behind Germany, where the equivalent employee income net of levies represents 70% of employer costs.

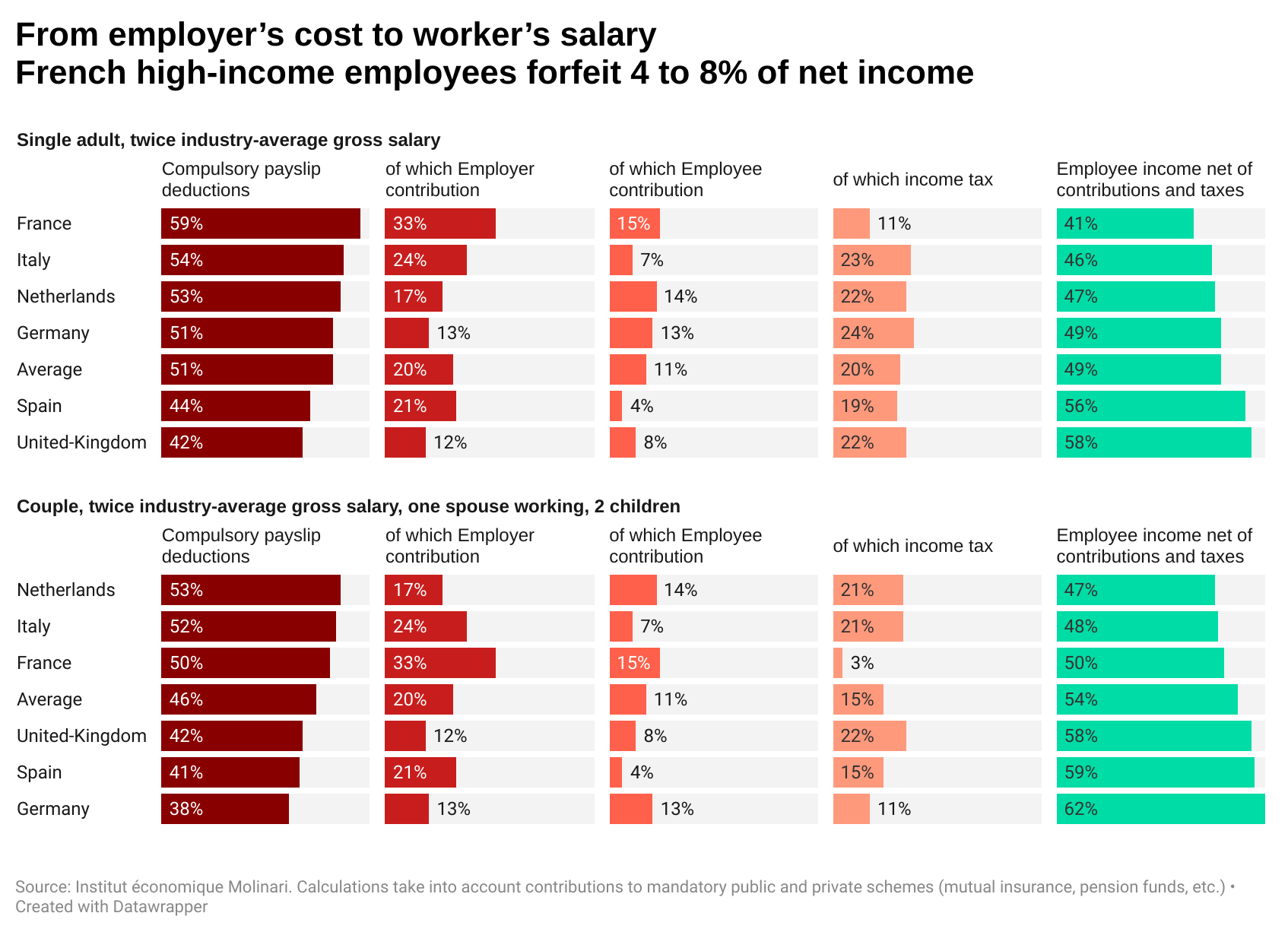

For high earners, France remains the worst destination, except for couples with a non-earning spouse and two children. For affluent families, the best locations are Germany, Spain, then France, Italy and the Netherlands.

France’s lack of price competitiveness is not explained solely by the quality of the social security it provides. French social security expenditures per capita (€12,200) are equivalent to Germany’s (€12,600) and lower than in the Netherlands (€13,500). As a proportion of French GDP (34%), these expenditures are not far from those of Germany (30%), Italy and the Netherlands (29%).

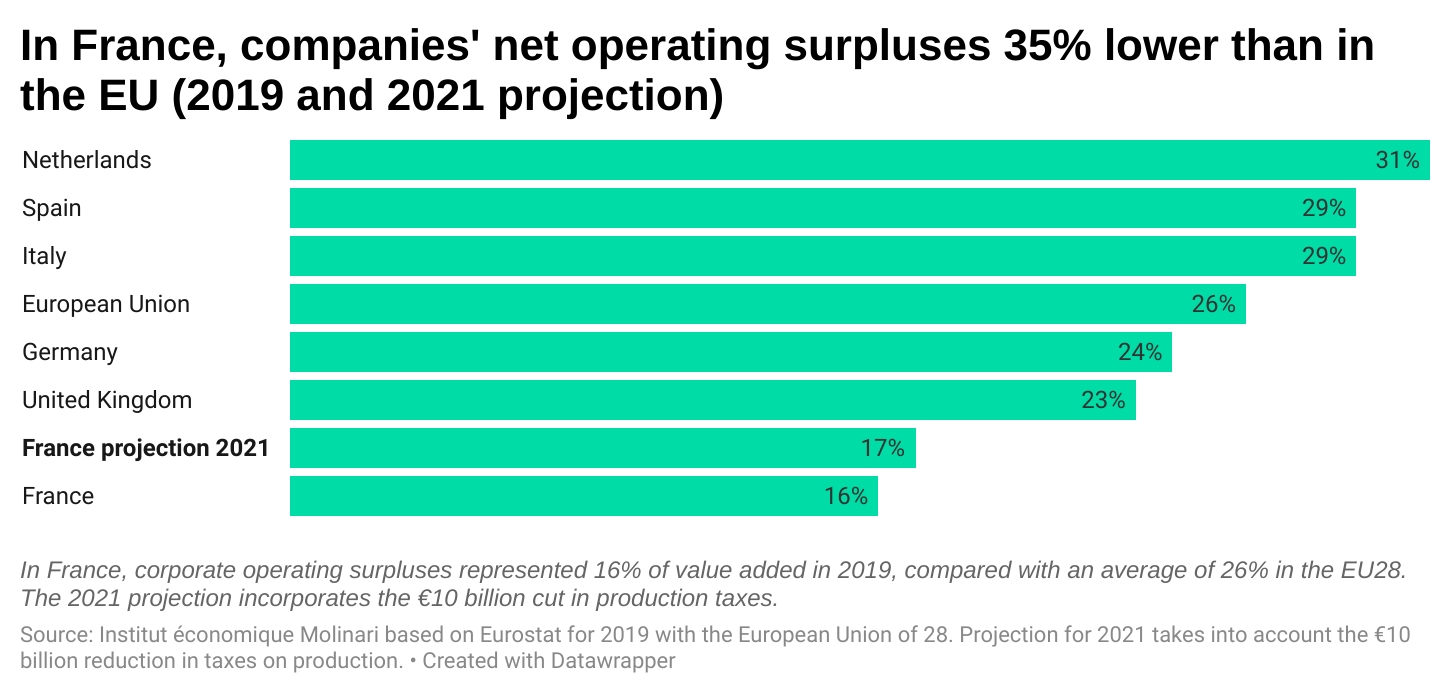

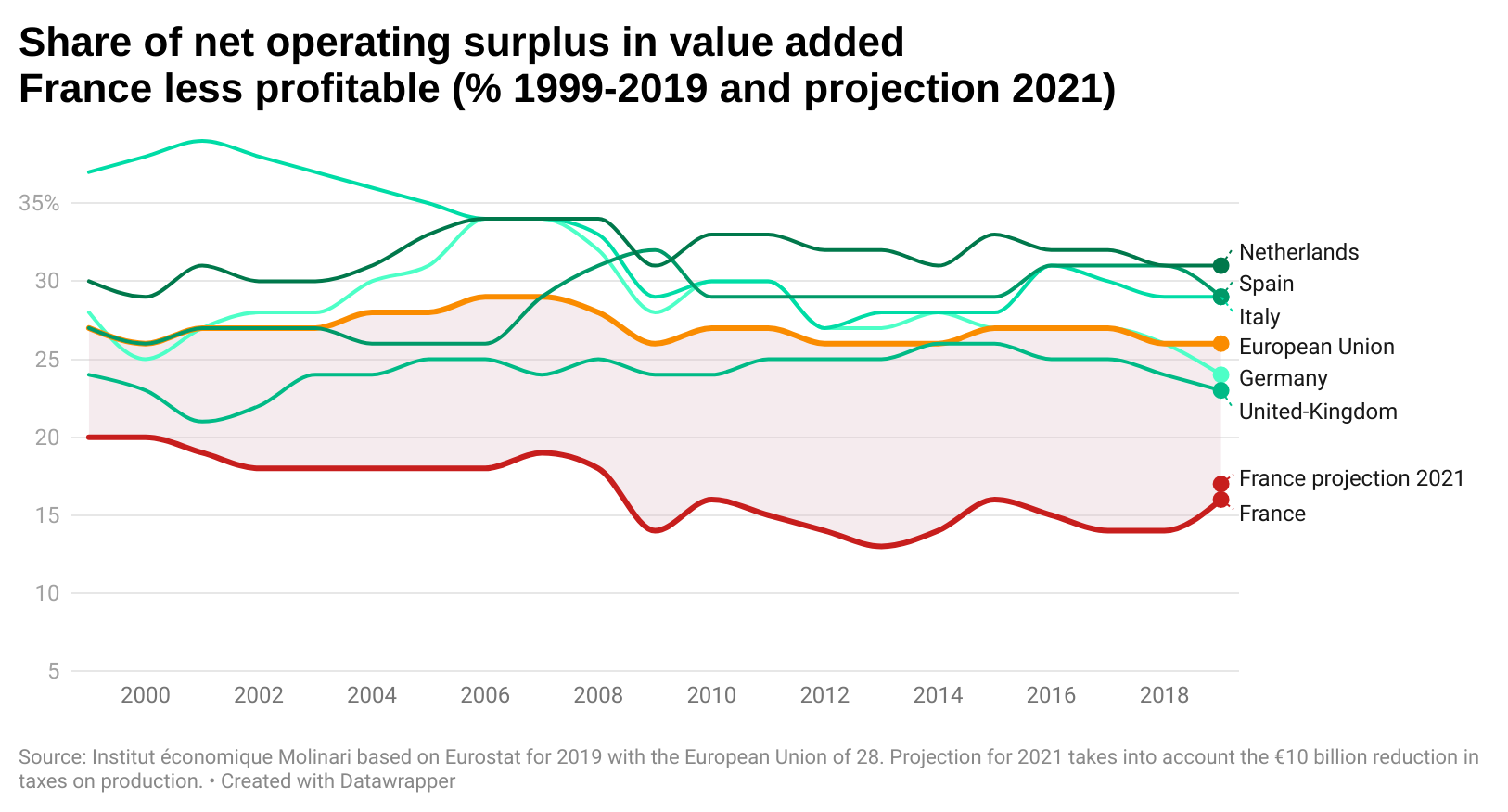

France 35% less profitable for companies

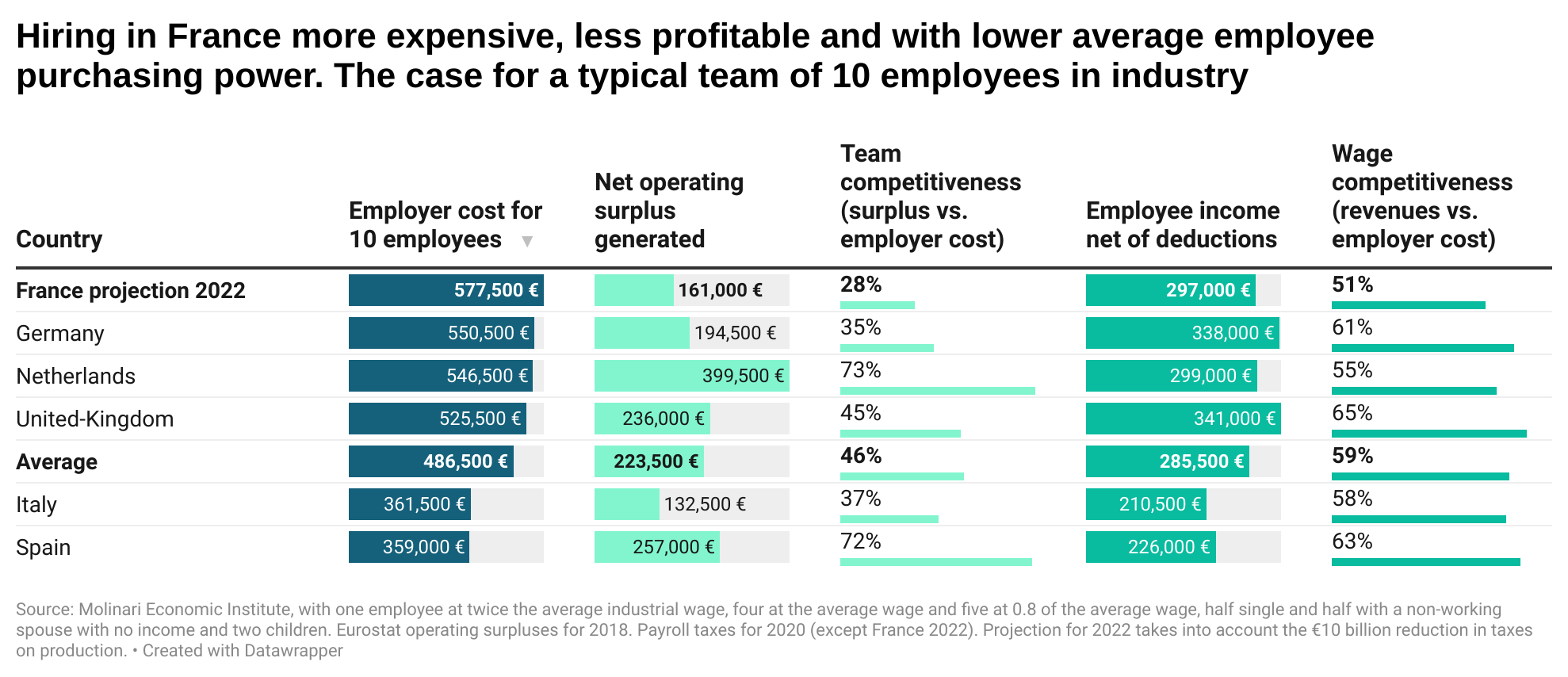

Despite the lowering of taxes on production, France remains 35% less profitable than the former EU28, 28% less profitable than the UK, 30% less profitable than Germany, 43% less profitable than Italy and Spain, and 45% less profitable than the Netherlands.

For labour costs, return on investment, and return on labour costs, France places either poorly or dead last

To minimise labour costs, Spain and Italy are the best choices, representing a 40% savings on payroll, thus allowing 60% more employees to be hired on the same budget. Next comes the UK (10% cheaper), followed by the Netherlands and Germany (5% cheaper).

To maximise returns on investment, head for the Netherlands and Spain, where profitability is more than twice as high, followed by the UK, Italy, Germany and, in last place, France. Though lowering production taxes does improve the situation, it cannot erase the gap in competitiveness with Germany and Italy, and France remains the worst choice of location.

In the race for the best ratio of employee purchasing power to employer cost, the United Kingdom, Spain, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands all cross the finish line before France, where wages net of compulsory deductions are 12% lower than in Germany or the United Kingdom, even though French employers spend more on their employees.

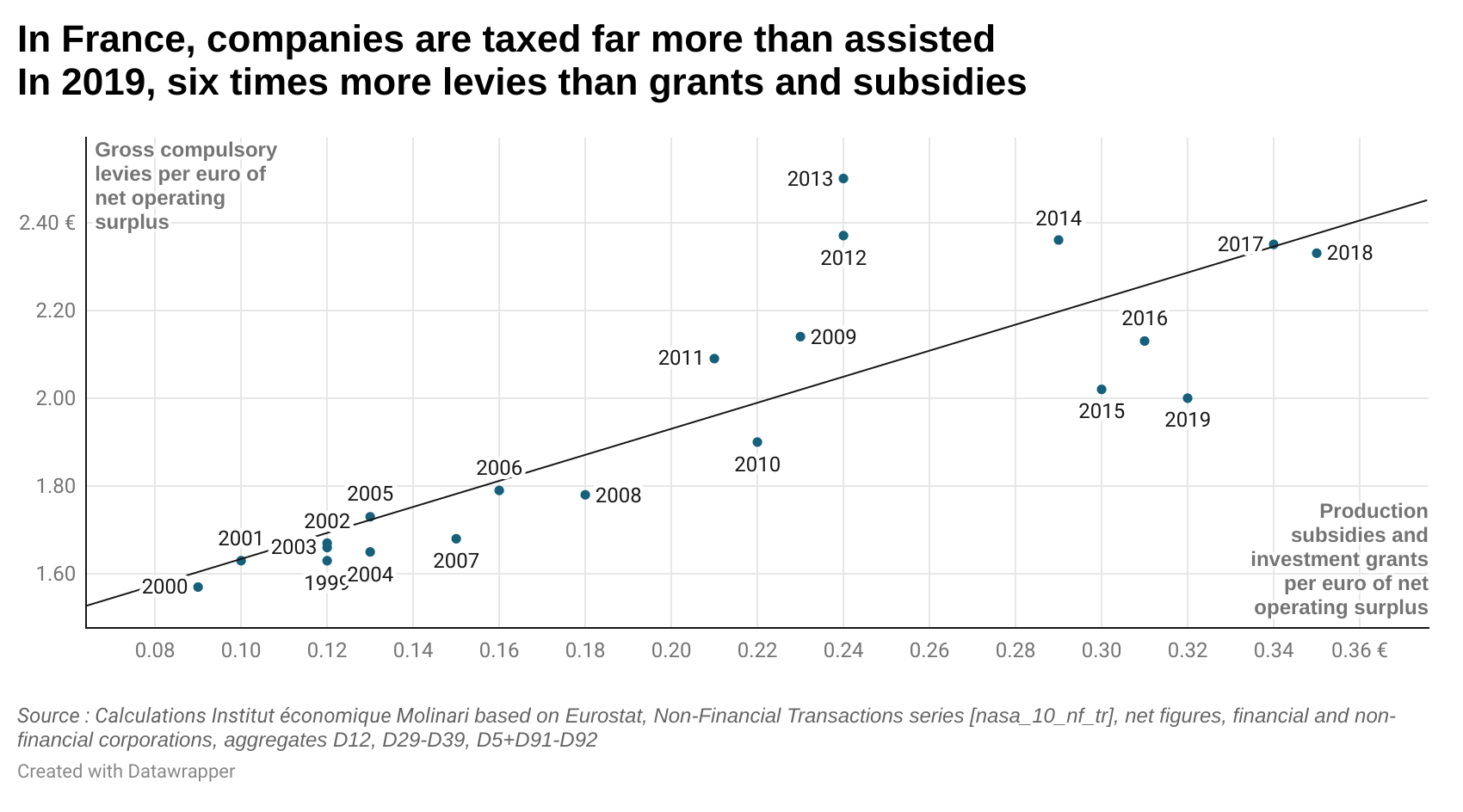

Taxation continues to penalise wealth creation in France

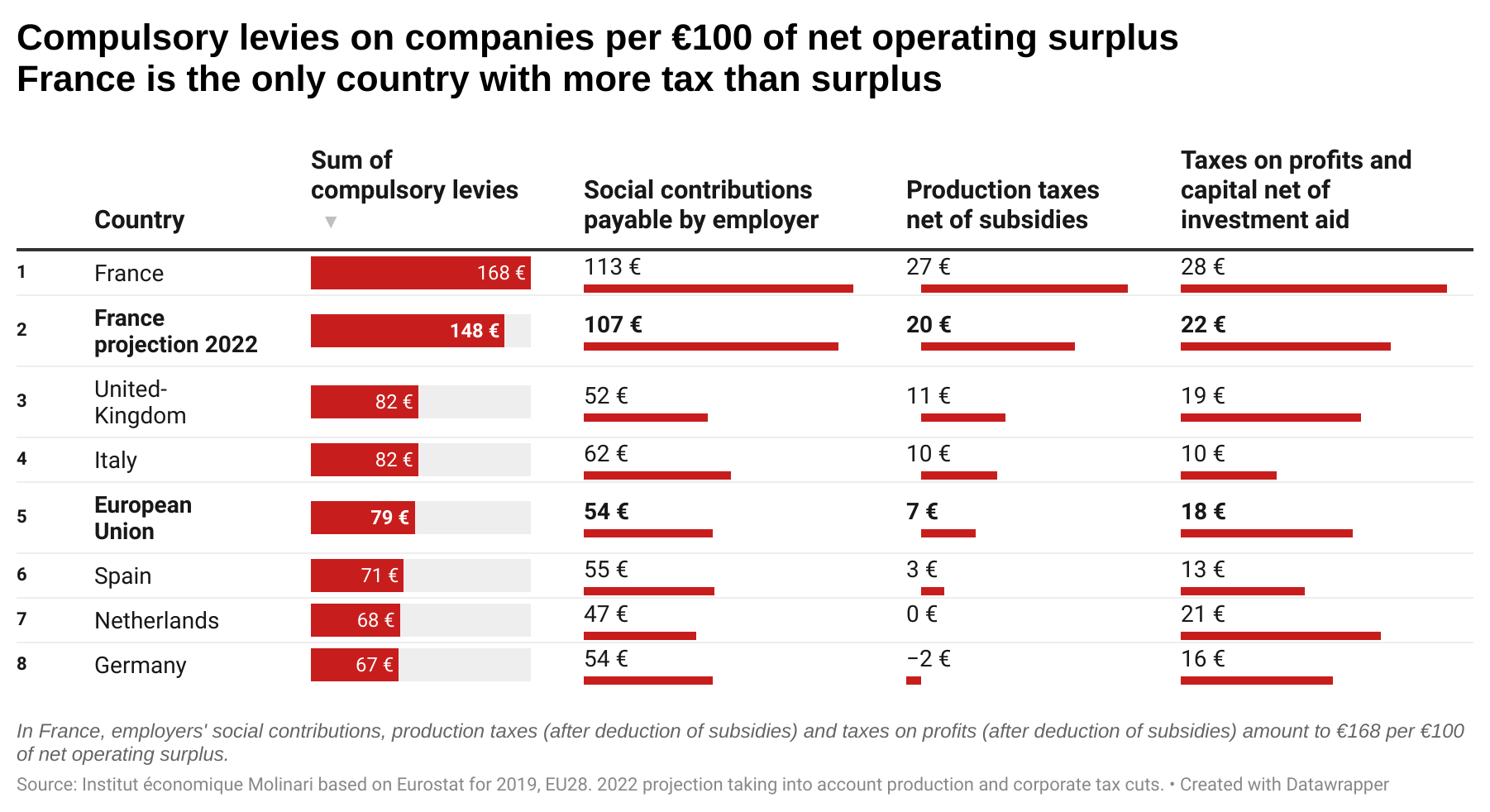

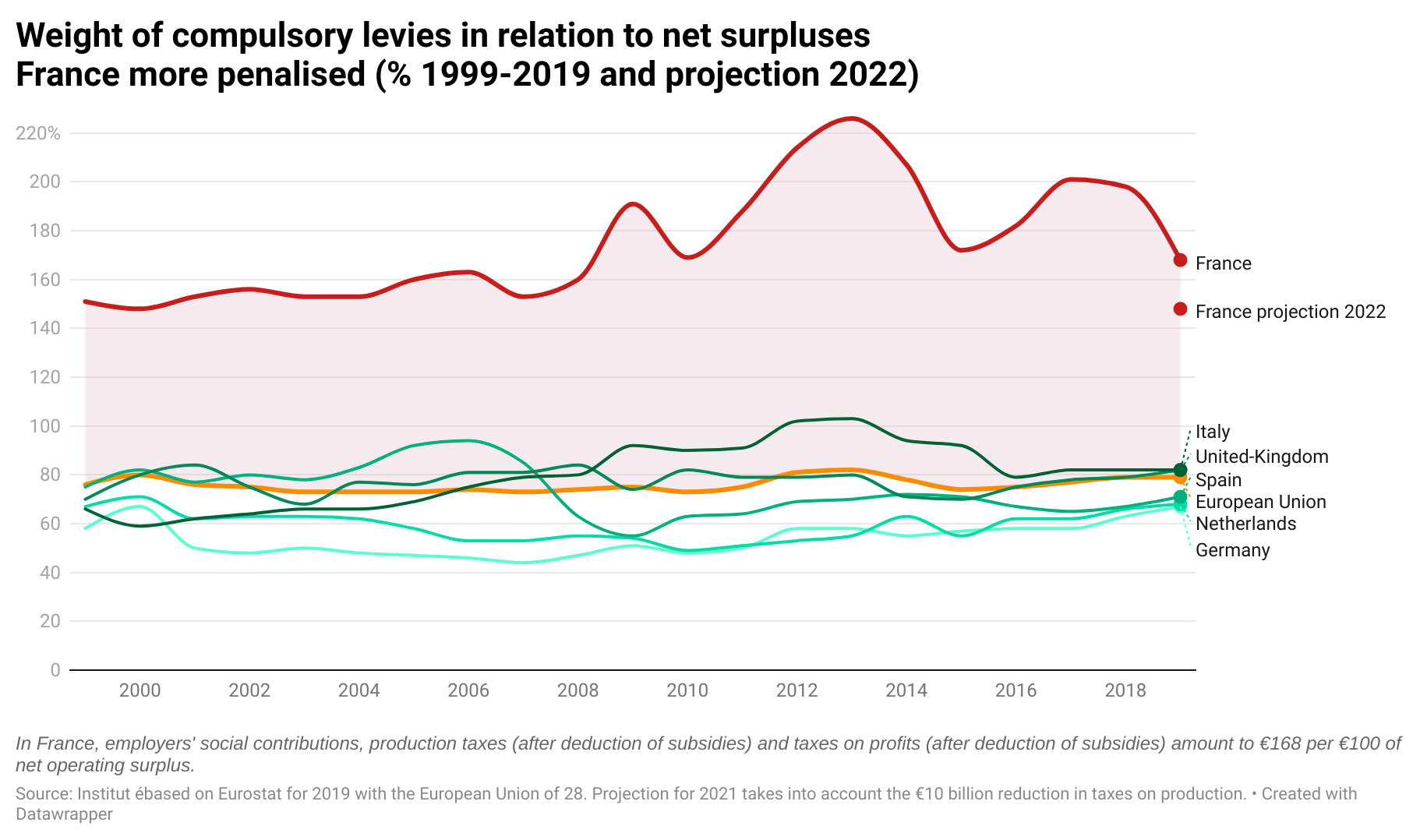

To realise a net operating surplus of €100 in 2019 (the last year before the crisis), the average French company had to pay €168 in compulsory levies net of subsidies, this while the average in the EU28 stood at €79. Taxes on production and employers’ social security contributions had twice the negative impact on competitiveness as in the rest of the EU.

The projections show that the reduction in production taxes (2021) and the generalisation of the reduction in corporate tax (2022) both improve the situation, but without eliminating the French handicap in price competitiveness linked to compulsory levies. In 2022, the average company in France will have to pay €148 in compulsory levies net of subsidies for every €100 in net surplus. Taxation will continue to outweigh companies’ net surpluses, making France an anomaly.

A supply-side policy illusion

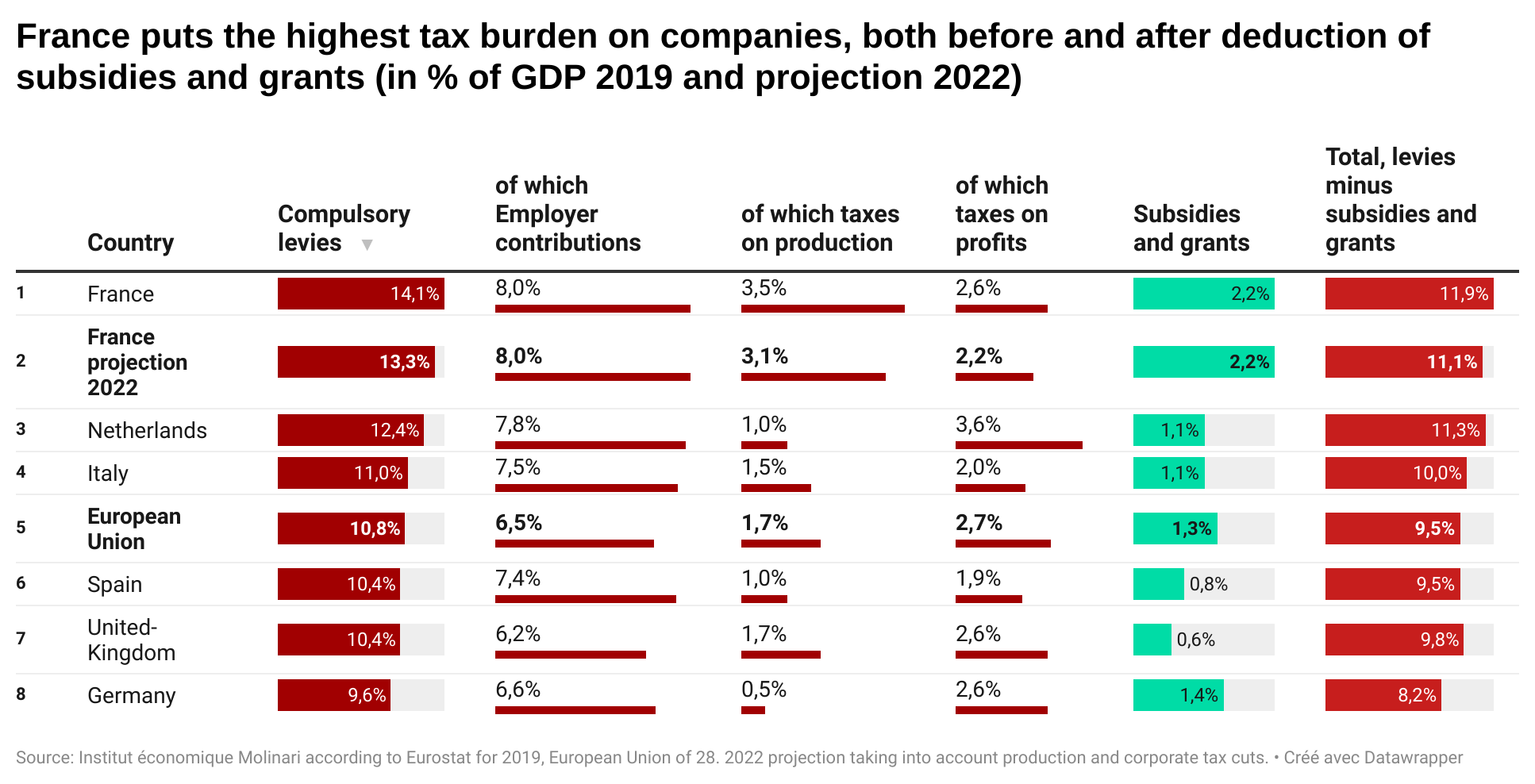

Even in 2022, the French economy will remain in a delicate competitive position: after deducting aid and subsidies, the taxation targeting companies will still be higher than that of its neighbours by 1.6% of GDP.

France’s economic policy is not friendly to the supply side. To deny this is to fall prey to an optical illusion, a reversal of cause and effect. Business subsidies have been put in place because the French tax system is so atypical, and these only compensate for about one third of the harmful effects of a tax regime which is both oversized and ill-conceived. This explains the persistence of structural imbalances (trade balance, public deficits, etc.) and excess unemployment when compared with the European Union.

Studies explain the persistence of imbalances

France continues to be uncompetitive for both companies and employees.

It is not by chance that EY’s studies on foreign investment show investment projects in France to be less favourable in terms of human resources (34 jobs created on average in France in 2020 compared with 48 in Germany, 61 in the United Kingdom and as many as 135 in Spain). Nor is it a coincidence that Rexecode’s work stresses the unprecedented nature of the deficit in the 2021 French balance of trade (€87 billion). Entrepreneurs can do the maths, and the rigour of the French tax system is an obvious deterrent.

The simultaneous occurrence of both abnormally high unemployment (300,000 more unemployed in France than the EU average in December 2021) and employee departures is no accident. Developments in cross-border employment are highly asymmetrical, with imbalances of ten to one (or worse) that attest to the lack of French competitiveness. According to the Bank of France, residents’ remuneration from outside France amounts to €22 billion per year. Going in the opposite direction, people living abroad earn barely €2 billion, i.e., eleven times less. According to INSEE, more than 360,000 people live in France and work abroad, while far fewer people from neighbouring countries work in France (around 10,000). Meanwhile, France has 2.9 million expatriates, a figure equivalent to that of the United States which has five times the population.

QUOTES

Nicolas Marques, Director general of the Institut economique Molinari, co-author

“In spite of the relaxations of recent years, French companies remain less profitable than their European competitors and the average French employee is still more taxed, which is detrimental to both job creation and purchasing power. As a result, structural unemployment remains abnormally high and deficits persist.

“Presenting French policy as generous to business is a biased view. It is because it taxes businesses and wealth creation more than its neighbours that it has particularly pronounced problems of competitiveness, employment and purchasing power. This has legitimised the implementation of palliatives sometimes presented cartoonishly as ‘supply-side policies.’

“The challenge remains to reduce taxes that penalise job creation and wage growth. A significant portion of our taxes on production, which are out of step in France, are passed on to employees. This tax system encourages wage moderation in France as well as relocation. It is a societal error.”

Cécile Philippe, President of the Institut economique Molinari co-author

“Some people present French economic policy as ‘pro-business.’ In fact, it is an attempt to compensate—very incompletely—for the perverse effects generated by a French tax system that is bloated and poorly designed.

“It is a juxtaposition of measures that seek to reduce inconvenience without addressing the underlying problem, and which are tantamount to crutches on a structurally unbalanced economy. These crutches benefit—beyond companies and shareholders—the working population and consumers. If we want to do without them, we must have the courage to enact reforms that allow the creation of more wealth.

“There are two priorities: to reduce taxes on production by €35 billion (to the level of our neighbours) in order to increase production, and to raise the retirement age and generalise collective capitalisation so that the financing of pensions does not have too great an impact on competitiveness.

“Companies do not need subsidies. They need a tax system that is compatible with the creation of wealth in France, and which is itself compatible with the social model to which our fellow citizens aspire. A real supply-side policy would be to stop penalising companies and workers in France.”

STUDY AND INFOGRAPHIC DATAWRAPPER

Link to study (in French) : https://www.institutmolinari.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/etude-competitivite_2022_fr.pdf

ABOUT THE AUTHORS AND METHOD

The study was authored by Nicolas Marques and Cécile Philippe of the Institut économique Molinari.

It covers France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK. In 2019, these six countries together accounted for 74% of wealth creation in the EU28.

This study uses data from Eurostat, which allows a homogeneous approach to the operating accounts of companies and to the different layers of taxation, whether it be taxes on production, employers’ social contributions, or income tax. Some of the calculations are based on net value added, which makes it possible to monitor what is paid to employees (gross remuneration), to the social security authorities (in the form of employers’ contributions) and to the company (net operating surpluses) once depreciation (the wear and tear on capital) has been deducted.

This work uses data from the OECD, supplemented by the authors according to national legislation to ensure consistency in the calculations, and integrates social security expenditures for both public and private bodies (mutual insurance, pension funds, etc.).

ABOUT THE INSTITUT ECONOMIQUE MOLINARI

The Institut économique Molinari is an organisation devoted to both research and education. Our mission is to promote better understanding of economic phenomena and challenges by making them accessible to the general public. To this end, we carry out scientific research, organise discussion groups, issue publications, and offer training and many other forms of education in the field. We work to stimulate the emergence of a new consensus by providing economic analyses of public policy that illustrate the value of better regulation and taxation. The IEM is a not-for-profit organisation funded by voluntary membership fees from individuals, foundations, and companies. It is intellectually independent and accepts no public funding.