In 2023, France will regain its title as champion of compulsory taxation on the average wage earner, ahead of Belgium and Austria

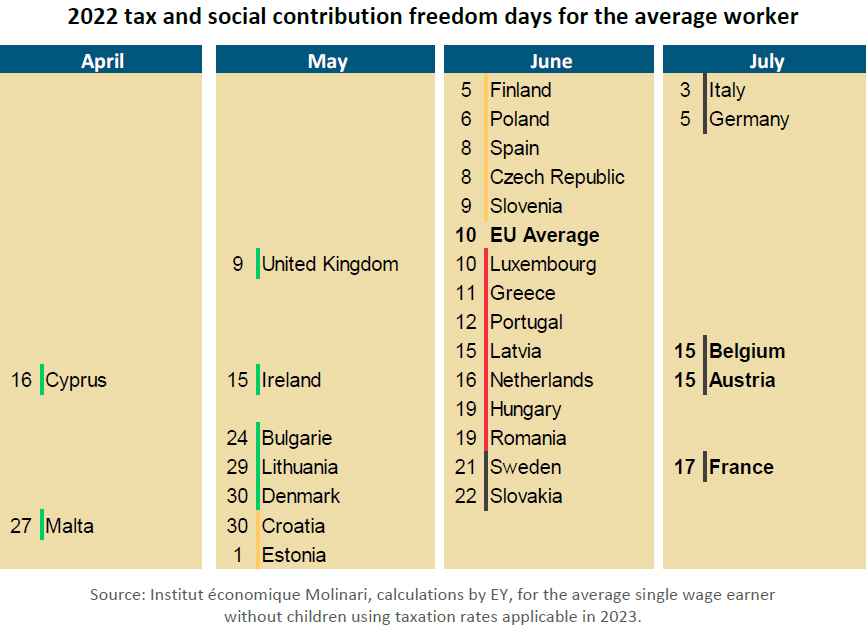

The average French employee works until July 17th to finance public services and collective benefits.

Paris, July 15, 2023 – Using data calculated by EY, the Institut économique Molinari is issuing its 14th annual study on the real social and fiscal pressures faced by the average wage earner in the European Union (EU).

This ranking has the distinct feature of providing figures for the current year on the social and fiscal pressure faced by the average worker, applying a solid, uniform methodology across all 27 EU member countries. It provides a firm understanding of the real impact of taxes and social contributions and the changes they are undergoing.

France returns to the top of the trio of countries that levy the most taxes on the average worker

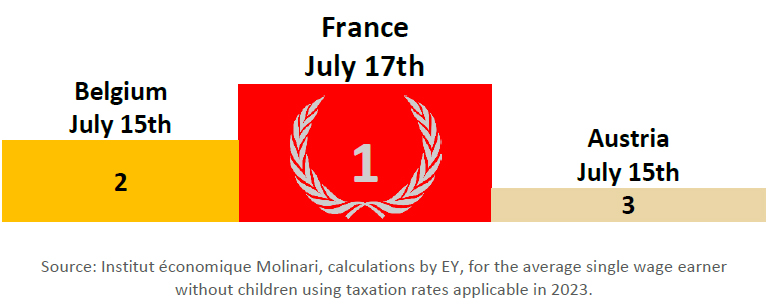

France will once again be the EU’s champion for compulsory deductions in 2023, with social and fiscal liberation occurring only on July 17th. Until that date, the average single employee has no direct control over how the fruits of their labour are spent. France is back in the No. 1 position it held from 2016 to 2020. The tax burden on the average employee is 54.1%. This is unchanged from with last year when France was No. 2 behind Austria, but since Austria has significantly lowered its tax burden, France will ascend to first place in 2023.

Belgium is second on the podium, with its social and fiscal liberation coming on July 15th. The former No. 1 in this ranking (from 2011 to 2015) became No. 2 (from 2016 to 2017) and then No. 3 (since 2018) thanks to its “Tax Shift.” It will return to No. 2 in 2023, with a social and fiscal pressure on the average employee of 53.5%, pending a significant tax cut in 2024 thanks to a new “Tax Shift.”

In third place comes Austria, with its social and fiscal liberation also coming on July 15th (though slightly earlier), and three days sooner than in 2022. Taxation of the average wage earner there stands at 54.4%, down significantly from last year (-0.9%). As of this year, the brackets on the income tax scale have been indexed to inflation, thus putting an end to the creeping increase in income tax brackets, known in Austria as “cold progression,” and meeting a long-standing demand from trade union representatives and business circles.

Over the past year, ten EU countries have seen a decline in taxes and social security contributions giving back at least one day of social and fiscal freedom. This was the case for Germany, Denmark, Portugal, and Sweden (+1 day), Austria and Greece (+3 days), Poland (+4 days), the Netherlands (+5 days), Finland (+9 days) and Croatia (+10 days).

Six countries are stable: Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Hungary, Lithuania and Romania.

The rest of the EU is experiencing year-over-year increases in compulsory levies leading to a loss of between one day (Cyprus, Spain, Ireland, Latvia, Malta, Slovakia, Slovenia, Czech Republic) and eight days’ social and fiscal freedom (Luxembourg).

In five European countries, taxes and social security contributions are higher than disposable income

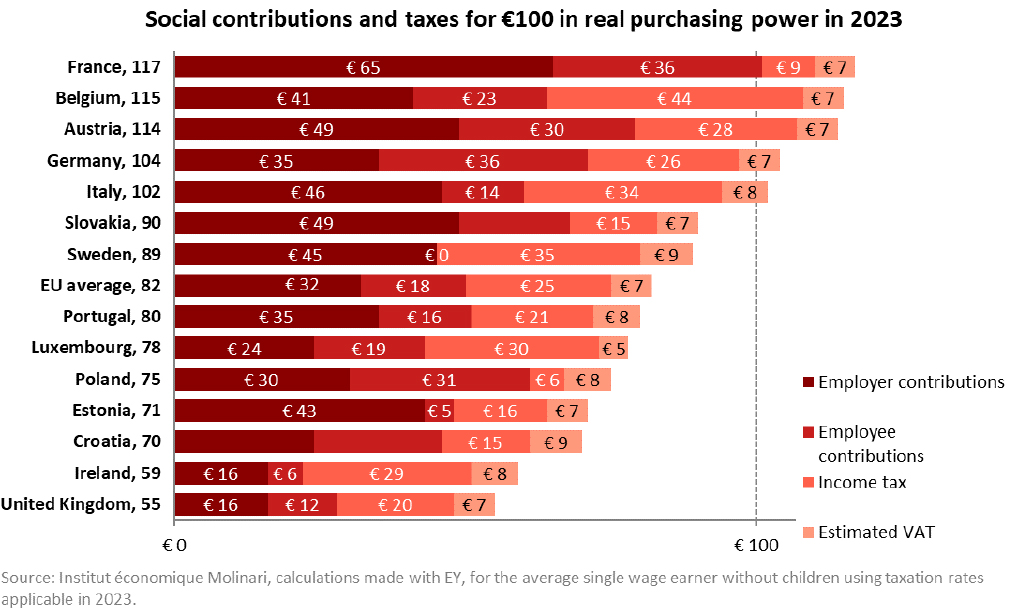

Before they achieve €100 of real purchasing power, the average French employee must first pay €117 in taxes and contributions, this compared with €115 in Belgium, €114 in Austria, €104 in Germany and €102 in Italy. By comparison, the EU average is €82.

For the average employee in the EU, the real tax rate continues to fall

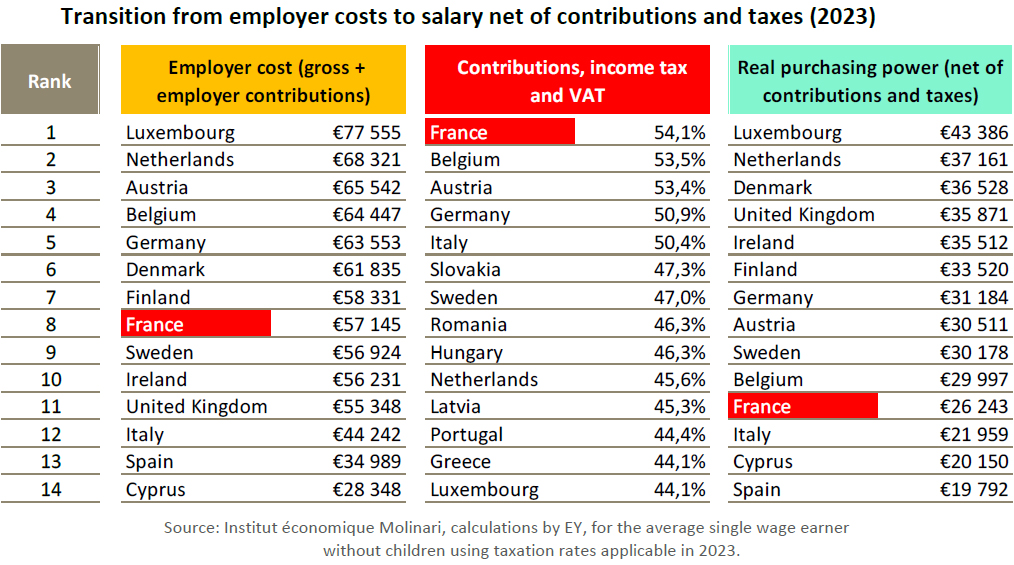

In 2023, the effective tax rate for employees in the EU-27 is 44.1%, down by 0.1% from 2022 and 1.5% from the peak in 2014.

In concrete terms, an average employee generating €100 of income before tax and charges will have to pay €44.10 in compulsory deductions in 2023. Ultimately, they will have €55.90 of real purchasing power at their disposal. This is €0.10 more than in 2022 and €1.50 more than in 2014.

For France, record social security contributions and particularly tight purchasing power

Most of the taxes paid by the average employee are employer contributions (55%) and employee contributions (31%), with income tax (8%) and VAT playing a lesser role (6%).

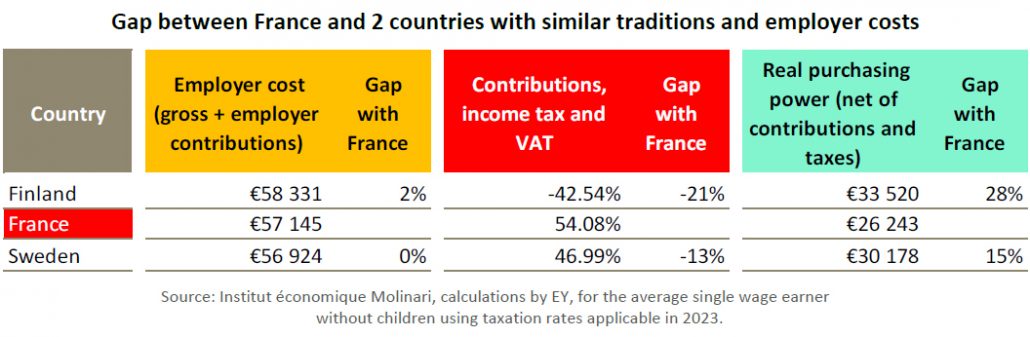

The average French employee costs his employer €57,145 (8th in the EU), but this work is so heavily taxed (54.1%) that they are left with just €26,243 net of compulsory deductions (10th in the EU).

In France, social security contributions (€26,665) are higher than net pay (€26,243). They represent 101% of take-home pay, the highest average in the EU at 50%.

So, while employers in France face labour costs on a par with those of the northern countries of the EU, the average employee has a net salary that is intermediate between those of the northern and southern countries.

France’s high level of taxation cannot be explained by better social protection and public services

The purchasing power of the average French employee is more restricted than in countries with a Beveridgian social tradition (United Kingdom and Ireland), but it is also lower with respect to northern countries with similar social traditions to ours.

For the same employer costs, the average French employee earns 15% to 28% less net salary than the equivalent Swede or Finn who also enjoys significant social benefits and public services.

The IEM’s study shows that French social and fiscal burdens cannot be explained by more attractive public services. French social and public benefits are not known for being “a good bargain.”

This is particularly true with respect to pensions, which account for 25% of public spending and €11,700 in social security contributions for the average employee. Funded almost exclusively on a pay-as-you-go basis, these yield lower returns than in countries where contributions are supplemented by savings. They cost French employees 30% more, with contributions representing 28% of gross salary compared with an EU average of 22%, for an additional gain of 10%, with a future replacement rate of 74% compared with 68% in the EU.

Compared with employees in the Netherlands who benefit from pension funds, the shortfall is quite significant. The net replacement rate should be 15% lower in France (74% of net in France vs. 89% in the Netherlands), while employees contribute 3% more (28% of gross in France vs. 25% in the Netherlands).

Education, which accounts for 9% of public spending, is another area in which France gets poor value for money. And the country’s position is deteriorating despite major collective investment. Though France spends €155 billion per year on education, it only ranks 17th out of 27 European countries. If France were to approach the most efficient countries in terms of matching training to the labour market, it could save up to €43 billion per year.

Higher taxes do not imply greater well-being

This study demonstrates that the social and fiscal burden in France is not synonymous with a better quality of life. It shows, rather, that life satisfaction is better in eleven countries with lower tax burdens: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Sweden.

ABOUT THE TAX FREEDOM DAY

Tax and social contribution Freedom Day is the date when the average employee stops, in theory, paying compulsory social contributions and taxes and can use the fruit of her labour as she pleases.

This indicator measures the date starting on which the employee becomes free to apply the fruits of her labour in the way she wishes and not the date starting on which the employee may stop “working for society.”

The particularity of this indicator of economic freedom is that it puts the situation of average EU wage earners in tangible form by bringing together each country’s taxation of labour (social contributions and income tax) and of consumption (VAT). Calculations of employer and employee social contributions and of income taxes are done by EY for each of the 27 EU countries.

QUOTES

Nicolas Marques, general manager of the Institut économique Molinari, co-author

“Despite adjustments to social security contributions and income tax in recent years, the average French worker remains among the most taxed in Europe, along with the Austrians and, to a lesser extent, the Belgians.

“Over time, average French workers have become the leaders in compulsory contributions, resulting in limitations on their purchasing power.

“It is an illusion to think that companies can achieve structural correction of this situation by increasing wages. Taxes and contributions account for 54% of gross pay, and when an employer pays an extra €100 to an employee, the latter receives only €46 once compulsory contributions have been paid.

“In order to restore employees’ purchasing power, we must find the courage to face these structural issues with systemic reforms that boost net wages.

“Taxes that penalise job creation and wage growth must be reduced further. A significant proportion of taxes on production, which are abnormally high in France, are passed on to employees in the form of less generous wage increases. These taxes are detrimental to both wealth creation and purchasing power, and represent societal errors.

“In terms of expenditures, we must diversify the financing of pensions, which in France is based almost exclusively on pay-as-you-go schemes detrimental to competitiveness and employment. In our neighbouring countries, a significant portion of pensions is financed by pension funds. This makes pension funding less costly for the economy, increases the value for money for both working people and pensioners, all while reducing wealth inequalities with an even wider sharing of the value.”

Cécile Philippe, president of the Institut économique Molinari, co-author

“Contrary to popular belief, high social contributions and taxes are not an indicator of better public services.

“French pensions, which absorb 25% of public spending, are more costly than in European countries that rely on both pay-as-you-go pension funds (the Netherlands, Sweden, etc.). Health and health insurance, which absorb 20% of public spending, suffer from overcrowding and an absence of innovation.

“Our education spending, which absorbs 9% of public expenditures, also suffers from poor value for money. France’s position is deteriorating, despite major collective investment. If France were to emulate the countries that optimise the balance between education spending and the labour market, it could save up to €43 billion per year.

“To spend money wisely, one must have to have the courage to verify the value achieved for price. But we have lost the habit of taking this common-sense approach and of correcting course when the value for money in collective services is inadequate.”

James Rogers, associate researcher at the Institut économique Molinari, co-author

“Despite the good news, French, Belgian and Austrian wage earners are still devoting more than half of the amounts distributed by their employers to social contributions and taxes.

“It’s worth asking why they are not getting the top schools, the best health care and the most generous pensions in return and why they are not the leaders in indicators of human development or well-being.”

RESOURCES

The study, La pression sociale et fiscale réelle sur le salaire moyen au sein de l’UE en 2022 (14ème édition, 46 pages) is available at the links below in French (EU and UK version) at:

https://www.institutmolinari.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/etude-fardeau-fiscal-eu-2023.pdf

A Datawrapper map is available: Real tax rate for the average employee in 2023

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/zFz3D/

As well as 3 Datawrapper tables:

- Shift from employer cost to purchasing power in 2023: https://www.datawrapper.de/_/cBbjx/

- Taxes and contributions per €100 of real purchasing power in 2023: https://www.datawrapper.de/_/P77TP/

- Breakdown of taxes and contributions in 2023: https://www.datawrapper.de/_/a5LFq/

An English version (Europe + South Africa, Brazil, Canada, United States, Japan, United Kingdom) will be published between now and September.

ABOUT THE INSTITUT ÉCONOMIQUE MOLINARI

The study was written by Nicolas Marques, Cécile Philippe and James Rogers of the Institut économique Molinari (IEM).

The Institut économique Molinari (Paris and Brussels) is an independent research and education organisation. It seeks to stimulate the economic approach in the analysis of public policy, offering innovative alternative solutions that favour the prosperity of all individuals making up society.

FOR INFORMATION OR INTERVIEWS, PLEASE CONTACT THE AUTHORS

Nicolas Marques, General manager of the Institut économique Molinari (Paris, French),

nicolas@institutmolinari.org, +33 6 64 94 80 61

Cécile Philippe, President of the Institut économique Molinari (Paris, French or English), cecile@institutmolinari.org, +33 6 78 86 98 58

James Rogers, Associate researcher at the Institut économique Molinari (Brussels, English),

james@institutmolinari.org, +32 497 946 840