What austerity?

Op-ed published on May 17, 2013, in the National Post (Canada).

In all the discussions in Europe about the consequences of so-called « austerity, » the only numbers presented as evidence that austerity measures have been implemented consist of statistics indicating that budget deficits have gone down during the past three years.

Indeed, they have. The average level of deficit as a percentage of GDP in EU countries in 2012 is much lower (4%) than it was at the height of the crisis in 2009 (6.9%).

For the Keynesian critics of austerity, this explains why most countries on the continent are still in recession, or close to it, and why unemployment is reaching record highs. Austerity is killing demand, killing employment, killing growth. The only way to restart the economy is to forget about the deficit and the debt and to go ahead with more stimulus spending.

There is however a fundamental confusion over the meaning of the word « austerity » which impedes a better understanding of the situation and precludes a more relevant debate over the causes of the crisis.

It should be obvious that there is no direct relationship between reducing the size of the deficit and reducing the size of government. A budget deficit can be reduced either by cutting spending or by increasing revenue. It can also be reduced if spending is cut a lot but taxes are cut only a little. It can be reduced even as spending increases if revenues increase even faster.

In practice, « austerity » can thus cover all kinds of situations with differing economic impacts. The term can apply just as well to growth as to reduction in the size of government.

It seems to be universally taken for granted that austerity measures have meant drastic spending cuts, coupled with some tax increases, the net effect being a downsizing of government. But is this really the case?

Governments keep growing

The latest Eurostat data indicate that there has only been a slight decrease of 1.7% percentage points in government spending as a proportion of GDP in the 27-member European Union since 2009. That proportion is, however, still four percentage points higher in 2012 than before the crisis started, 49.4% compared to 45.6 % in 2007.

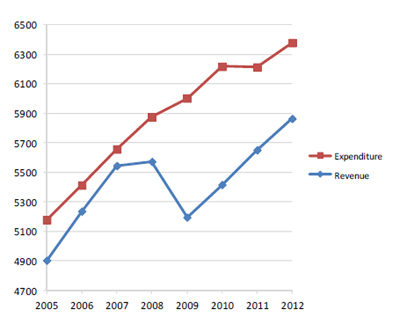

In nominal terms, government spending has never stopped rising in the Union as a whole since the beginning of the financial crisis, except in 2011 when it remained constant (see Figure). Spending grew by 6.3% in the last three years, in other words during the period when « austerity » policies were supposed to have been applied.

Thus, whenever finance ministers announced budget cuts, they were actually referring not to absolute reductions in total spending but simply to spending increases that were lower than what was previously planned or to cuts that were offset by more spending elsewhere.

Total general government revenue and expenditure in billions of euros

European Union (27 countries)

Source: Eurostat, Government revenue, expenditure and main aggregates.

There are only a handful of countries where nominal expenditures really fell between 2009 and 2012, including Greece and Portugal. However, both in nominal terms and in proportion to GDP, the governments of these two countries spent more in 2012 than in 2007.

With no net decrease in spending, the deficit reductions observed in most countries must have occurred because tax revenues went up faster than spending. And that is precisely what the Eurostat data show, with revenues up 12.9% from 2009 to 2012, double the pace of increase in public spending.

Governments have not been borrowing as much-although they still borrow heavily, and public debt keeps increasing. Instead, they tax their citizens more to fund their growing expenditures.

Austerity measures never applied

There is thus an inescapable fact that everyone seems to want to ignore: Governments in almost all European Union countries are as large as they were when the crisis started in 2007 or even larger today. If we define austerity as the measures taken to reduce budget deficits, then in that sense austerity is indeed responsible for the crisis.

If, however, we define it more properly as policies bringing about a reduction in the size of government, then these policies cannot be held responsible for the crisis because they were never applied.

Keynesians will, of course, regret that there haven’t been even larger spending increases, greater borrowing and expanded deficits in the past few years to stimulate the economy.

But, from a free-market perspective, bloated governments and higher taxes certainly help explain why European economies are still in the doldrums, several years after the financial crisis.

What Europe needs is smaller governments, not just in terms of public spending but also as regards deregulation of the job market and other structural reforms to encourage entrepreneurship, private investment and job creation. There will be sustained growth in Europe only when governments, and not citizens or businesses, finally bear the brunt of austerity.

Martin Masse is Associate Researcher at the Institut économique Molinari.